Tom O’Connor writes

Dublin’s Lesser Known Attractions

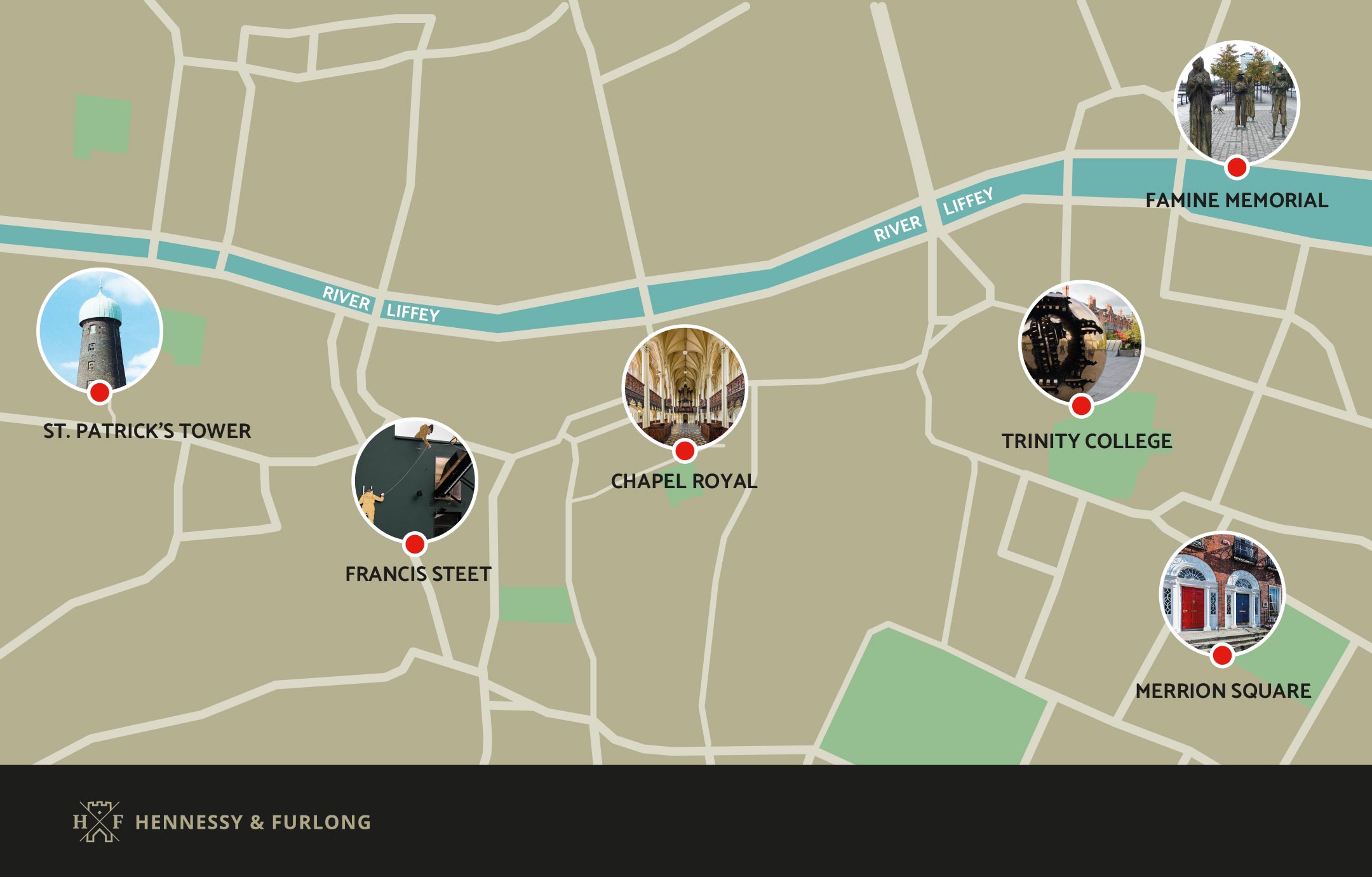

SAINT PATRICK’S TOWER

In medieval times, Dublin city was walled for protection and administered by a corporation, which controlled trade and levied taxes within the walls. Beyond the walls, lying outside of the Corporation’s control, areas were established called ‘liberties’. From his roost near the corner of Thomas Street and Watling Street, making a striking contribution to the iconic skyline, our patron saint watches over The Liberties. Standing at a majestic 135 feet high, although sadly it has now lost its sails, this former smock windmill was once the largest in Europe.

It is quite a distinctive and poignant, reminder of the industrial built heritage of the area and its associations with the distilling and brewing industries.

©Tom O’Connor

‘Smock’ mills, with their sloping sides, take their name from the distinctive smocks worn by artisan farmers in the Netherlands from where this style of mill originated.

The original construction date is unknown, it has been suggested that it was originally part of a corn mill before 1757, when Peter Roe purchased a then small existing distillery on the site. It was rebuilt in 1815 and converted to steam power. Presumably used to grind malted barley, it powered a distillery that by 1887 had become one of the largest in Europe, covering some seventeen acres and producing two million gallons of whiskey annually for the very lucrative export market and local consumption.

In 1889 the Roe Distillery, Jameson and the Dublin Whiskey Distillery merged to form the Dublin Distillers Company and the copper cupola with an effigy of Saint Patrick was added to the tower by the distillers.

Tough competition from Scotland and the advent of prohibition in America had an enormous impact on the Irish distillery business, by the mid 1920’s the distillery ceased production and by 1949 the distillery and all of its mature stock was gone. The site was then bought by the Guinness family and now forms part of The Digital Hub.

A pear tree, said to be of 19th century vintage, still flourishes beside the tower.

FRANCIS STREET

A short saunter from Saint Patrick’s Tower and down through The Liberties leads us to Francis Street which is one of the most historically significant streets in the city, dating mostly from the 14th century, and named for the Abbey of Saint Francis founded there in 1235.

Towards the end of the 17th century, many of the houses here were of the type known as ‘Dutch Billys’, reputedly named after William of Orange, the tall and narrow, gable-fronted houses then so popular in Dublin.

During the last quarter of the 18th century the street was mainly inhabited by very prosperous merchants, manufacturers and traders, whose opulence became almost a byword in the city. A testament to its important standing in the fabric of the city is further highlighted by the fact that Dr. Johnathan Swift, author of Gulliver’s Travels and Dean of Saint Patrick’s Cathedral, addressed his famous and inflammatory Drapier’s Letters – ‘From my shop in St. Francis Street…….’

By the middle of the 19th century the various industries established in the neighbourhood fought a tough fight for existence. The street became a hive of small shops, including nearly twenty grocery shops, several dairies, boot and brogue-makers, tobacco and snuff producers, pipe-makers, soap-boilers, whip-makers, tailors, drapers and haberdashers. There were also some large factories dealing in bran, butter and general provisions and of course the Sweetman’s brewery dating from 1755.

©Tom O’Connor

By 1900 the street was in serious decline and became a Liberties slum with no fewer than forty five houses turned into multi-occupancy tenements, the few remaining shops became much more workaday and housed many manufacturers of beds, cabinets and household furniture. Towards the latter half of the 20th century the antiques trade began drifting towards Francis Street from the quays, and today the street has the highest concentration of antique dealers in Ireland. One of the most striking shopfronts on the street is that of O’Sullivan Antiques, founded in 1991. Several art galleries also have their home on Francis Street.

Constantly in flux much of the street’s future depends on the regeneration of the now derelict Iveagh Market, which had been a thriving market since 1906.

Other notable landmarks are the Church of St Nicholas of Myra, patron saint of brewers, and Myra House where the Legion of Mary was founded in September 1921. This organisation would have a massive effect on the city of Dublin, spearheading the campaign to close the notorious Monto district of the city.

©Tom O’Connor

THE CHAPEL ROYAL

The City of Dublin grew from two small settlements at the confluence of the River Liffey and the River Poddle. The original settlements were known as Áth Cliath, The Ford of Hurdles, a crossing place made of hurdles of interwoven saplings straddling the low-tide Liffey, and Dubh Linn, The Black Pool, which existed beneath the present site of the coach house and gardens of Dublin Castle. Within the walls of the castle there are many historic attractions, not the least of which is The Chapel Royal.

Built in the pointed Gothic Revival style it served as a private chapel for the viceroy, his family and his court. The services here were attended by much pomp and ceremony and the viceroy could reach his pew in the chapel gallery from the State Apartments, without going out of doors, by means of a battlemented corridor which skirts the south side of the medieval Record Tower.

©Tom O’Connor

The doorway leads into the main body of the chapel where all the interior vaulting and columns are cast in timber and treated with a faux Stuc Pierre, a type of paint wash applied to resemble marble.

Master stuccodore George Stapleton was responsible for the fantastic plasterwork of the fan vaulting, made to imitate medieval stone tracery. The beautifully carved oak galleries are the work of Richard Stewart and display the coats of arms of all the viceroys from 1172 onwards.

©Tom O’Connor

Stewart appears to have been a difficult character and after a dispute with Francis Johnston about carving the Wellesley arms in the Chapel was labeled ‘Stewart the mad carpenter’. Later coats of arms can be seen on the chancel walls and in the stained-glass windows.

Worth recounting is the local legend that when all the spaces were filled Ireland would be free and it is indeed remarkable that the last available space should have been filled with the arms of the last viceroy, Lord FitzAlan Howard, in 1922.

The floor is elegantly paved in black and white stone, set on the diagonal. Some of the original pews are now in the entrance hall of the State Apartments, and the enormous pulpit that dominated the chapel now resides in Saint Werburgh’s Church of Ireland.

The four central panels of the east window contain early stained-glass, depicting scenes from the Passion of Christ. Believed to be of Russian origin, these windows were purchased on the continent and imported by the viceroy, Earl Whitworth, and presented to the chapel.

The first service was held on Christmas Day 1814 and it became known as the Chapel Royal after King George IV attended service in 1821. The viceroy, his family and his court worshiped here until 1922.

In 1943 the chapel was reconsecrated as the Church of the Most Holy Trinity, one of the few churches in Ireland to have changed from Protestant to Catholic. More recently, after major refurbishment, the chapel was deconsecrated and is now mainly used for ceremonial occasions and musical recitals.

MERRION SQUARE

Of Dublin’s five Georgian squares Merrion Square is easily the most supreme. It is not really a square, only Mountjoy Square can claim that distinction. All of the original houses on the square have survived to the present day except for Antrim House, the second grandest, which was demolished to make way for the Holles Street Maternity Hospital. Their external features, doors, fanlights, windows, balconies and railings have hardly changed. The same is true for their interiors which contain some magnificent rooms, stairs, fireplaces, plasterwork and frescoes. Three sides of the square are lined with redbrick townhouses and the west side abuts Leinster House, Government Buildings, the National Gallery and the Natural History Museum. The central garden, once a private garden, is now a public park. In the early 18th century the area was marshy farmland on the edge of the city, fashionable Dublin congregated on the opposite side of the River Liffey.

© Tom O’Connor

This was all set to change in 1745 when James FitzGerald, Earl of Kildare and later Duke of Leinster, decided to build the largest aristocratic residence in Dublin, second only to Dublin Castle, on the south side of the Liffey. Lord Kildare upon being advised that he was making a grave mistake, setting up home in such an unfashionable location, retorted ‘They will follow me wherever I go.’ Which indeed they did when aristocrats, bishops and the wealthy sold their Northside townhouses and flocked to the Southside. As a result three new residential squares appeared on the Southside, Merrion Square, St. Stephen’s Green and the smallest and last to be built Fitzwilliam Square.

In 1762 Merrion Square was laid out to the designs of surveyor Jonathan Barker, commissioned by the estate of Viscount FitzWilliam. Building began on the north western end and was almost complete by the beginning of the 19th century. The designs called for a high degree of uniformity in style of the houses to be built. Each house was to be a four storey over basement with the sash windows and front doors all of the same proportions. All of the materials used would also have to be uniform.

©Tom O’Connor

Richard FitzWilliam was a shrewd operator, bricks used for the front of the houses were produced in his extensive brickworks at Merrion Gates, Sandyford. Granite for the pillars, front steps, door frames, the window sills and surrounds came from his quarries at Ticknock Mountain. No alternative materials were permitted. Houses were generally built in groups of three and the developer would take up residence in one of the houses and lease out the remaining properties. However, as the square developed over a long period of time, changes in taste are evident in the proportions of doors and windows, and inclusion of decorative ironwork. These sometimes subtle flashes of nonconformity only serve to enhance the overall charm, character and ambience of the square.

©Tom O’Connor

TRINITY COLLEGE

Dublin was just beginning to function as a capital city in 1592 when Trinity College was established, outside the city walls, as an autonomous corporation by royal charter of Queen Elizabeth l. The foundation of the university was deemed an essential step for Irelands inclusion into the mainstream of European learning and in bolstering the Protestant Reformation. Throughout its turbulent history the university has played a major role across all the major disciplines in the arts and humanities, business and law, engineering, science and health sciences. From Theobald Wolf Tone to Samuel Beckett the university has produced some of the most outstanding politicians and writers of the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries. Home to the Book of Kells, the university is world renowned for its collections of books held in The Old Library and the Long Room which houses some 200,000 of the oldest volumes.

However, a walk through the cobbled stones of Trinity College will reveal other treasures: the Museum Building constructed from a vast number of contrasting forms of stone and the eclectic, nationally important, specimens housed in the Secret Zoo. The outdoor Campus Art trail incorporates work by some of the world’s most significant modern sculptors, Henry Moore, Alexander Calder, Eilis O’Connell and Sebastian. The bronze ‘Sfera con Sfera’ (pictured below) by Arnaldo Pomodoro sits in the forecourt of The Berkeley Library, known locally as the ‘Pomodoro Sphere’, this sculpture underwent major conservation in 2008.

In New Square ‘Failing Better’ by Rowan Gillespie pays homage to the flying experiments of George FitzGerald, Professor of Natural and Experimental Physics, in the late 19th century. These were mostly unsuccessful but always optimistic. This flying machine is a horse which develops wheels and then propellers, it will never really fly just as Professor FitzGerald’s machine never really flew but he at least dared to try. It brings to mind the words of Trinity College alumnus, Samuel Beckett “Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.”

© Tom O’Connor

THE GREAT HUNGER

Clay is the word and clay is the flesh

Where the potato-gatherers like mechanised scarecrows move

Along the side-fall of the hill – Maguire and his men.

These opening lines from Patrick Kavanagh’s ferocious poem The Great Hunger still resonate with the long-term emotional and psychological consequences of the famine on the national psyche. An Drochshaol, the hard times, is often attributed to a ‘natural catastrophe of extraordinary magnitude’, however the real cause was in the structures of the island’s political, economic and cultural landscape.

An indifferent colonial government, absentee aristocratic landlords and an ethnic underclass bereft of rights and land created a system which forced Ireland’s peasantry into a monoculture, since only the potato could be grown in sufficient quantity to meet their nutritional needs.

© Tom O’Connor

Successive failures of the potato crop from 1845 onwards caused a period of mass starvation and swelled the ranks of the Irish diaspora, an already intrinsic part of Irish life.

Before it had run its awful course, more than one million people had perished and two million had fled the island.

Although it should be emphasised that pre Black ’47 Dublin never had to face the scale of the famine horrors experienced in Connacht and Munster, nevertheless upwards of 60,000 of the migrant poor were in receipt of outdoor relief at the height of the city’s famine crisis.

They gathered in tenement areas and brought with them Typhus, Dysentery and Cholera so that disease rather than hunger now became the primary killer. Even the aristocracy were vulnerable to infection and many died without ever knowing lack of food.

© Tom O’Connor

The location of “Famine” by Rowan Gillespie in Dublin is a particularly appropriate and historic choice. Some 210 emigrants, forced to flee from the hunger and poverty of the hard times, set sail from Custom House Quay aboard the “Perseverance” on St. Patrick’s Day 1846, one of the earliest and safest of the voyages. But, alas, not the last.

ARTIST’S BIOGRAPHY

TomO’Connor (°1967, Wexford, Ireland) is primarily a lens-based artist.

By applying abstraction, O’Connor develops forms that do not follow logical criteria, but are based only on subjective associations and formal parallels, which incite the viewer to make new personal associations.

By choosing mainly formal solutions, O’Connor makes work that deals with the documentation of events and the question of how they can be presented.

The results are deconstructed to the extent that meaning is shifted and possible interpretation becomes multifaceted. He creates intense personal moments masterfully crafted by means of rules and omissions, acceptance and refusal, luring the viewer into a world of ongoing equilibrium and the interval that articulates the stream of daily events.

O’Connor’s work is an investigation into representations of concrete ages and situations as well as depictions and ideas that can only be realised in photography. By emphasising aesthetics, he approaches a wide scale of subjects in a multi-layered way, directly responding to the surrounding environment and using everyday experiences from the artist as a starting point. Often these are framed instances that would go unnoticed in their original context. Moments are depicted that only exist to punctuate the human drama in order to clarify our existence and to find poetic meaning in everyday life. At times, disconcerting beauty emerges.

O’Connor’s photographs are often about contact with architecture and basic living elements. Energy, space and landscape are examined in less obvious ways and sometimes developed in absurd ways. In a search for new methods to ‘read the city’ associations and meanings collide. Space becomes time and language becomes image. His works question the conditions of appearance of an image in the context of contemporary visual culture in which images, representations and ideas normally function. His images urge us to renegotiate photography as being part of a reactive medium, commenting on themes in our contemporary society.

By contesting the division between the realm of memory and the realm of experience, O’Connor absorbs the tradition of remembrance art into daily practice. This personal follow-up and revival of a past tradition is important as an act of meditation.

Tom O’Connor currently lives and works in Dublin.

DISCOVER A HIDDEN IRELAND

Our Journal Writers are passionate about the special people and their special homes that inspire them to write and share their experiences. Join our club of fellow travellers and heritage enthusiasts reading their stories of discovery around Ireland.