THE COLOURFUL LIFE OF AN IRISH ARISTOCRAT

A Fortune at Fifteen

For three hundred years Curraghmore House has been the seat of the Beresfords, Marquesses of Waterford, and for three hundred years before that the seat of the Powers, Lords Power, Earls of Tyrone and Viscount Decies.

The entrance tower dates from the 15th century, the remainder of the house from the 18th century. It has the largest and most spectacular courtyard in Ireland, and is surrounded by two and a half thousand acres of unspoilt gardens, demesne, farmland and forestry.

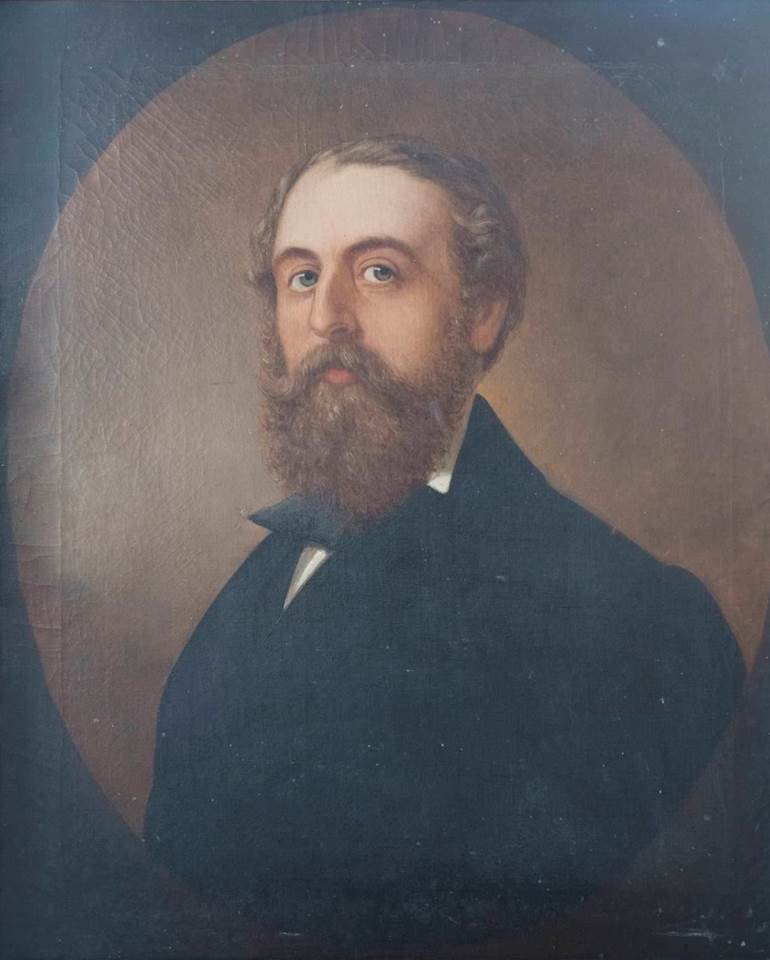

In the course of its six centuries, Curraghmore has produced many colourful men and women. None is remembered more vividly in local tradition than this man, Henry de la Poer Beresford, third Marquess of Waterford.

I feel he deserves to be considered in his own right. This journal article for Hennessy & Furlong is based principally on the work currently being undertaken on the archives at Curraghmore by William Fraher, Marianna Lorenc and myself.

Henry Waterford’s eccentric behaviour, bordering at times on instability, is due in my opinion to two factors. First, through his mother Lady Susanna Carpenter he inherited all the wildness of her mother’s family, the Delavals of Northumberland in England. Secondly, he was a younger son who was not expected to inherit the titles or estate.

However, during his teenage years his life began to change with bewildering rapidity. His elder brother died in 1824, just short of his fourteenth birthday, leaving Henry the heir; his father died in 1826, in the aftermath of the bitterly contested Beresford-Stuart election in Waterford County; his mother died in 1827; and in 1828 his elder sister Sarah left for England as the wife of Henry Talbot, later Viscount Ingestre. By the time he was eighteen, Henry was the master of vast estates, with little control over how he should exercise his power.

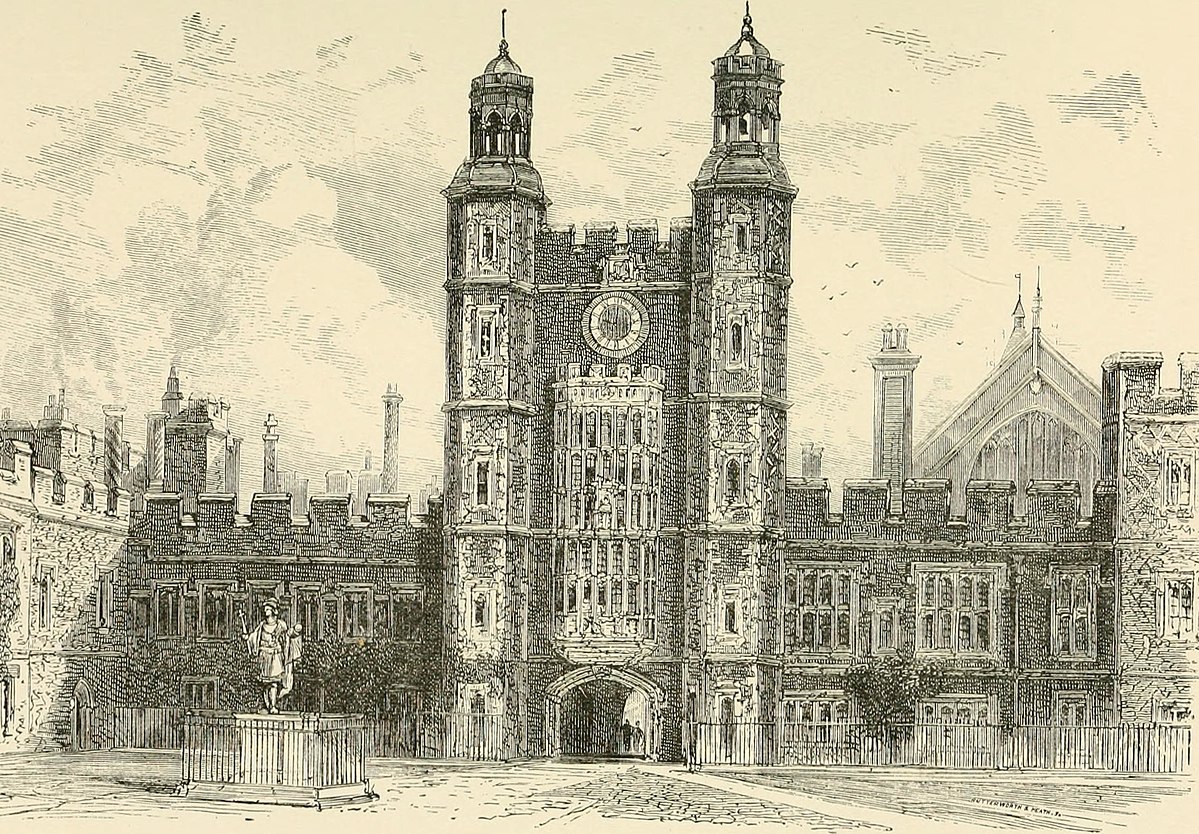

He was educated at Eton College in England under the infamous Dr Keate. A gifted oarsman, in his final year he stroked the college eight to victory in the annual race against Westminster.

An Aristocratic Playboy

The 1830s were the decade of his wildest exploits. In 1835 he and his twenty-one-year-old brother John (a future clergyman) sailed to New York in their yacht, and in a drunken spree smashed windows, lamp-posts, passers-by, and constables, before being finally overpowered and dragged off to jail, whence they were bailed out by the British consul the following day. A voyage to Norway two years later resulted in similar mayhem, but the constables of Bergen were made of sterner stuff than their American counterparts, and the Marquess’s life was nearly ended by a crack on the head from a spiked truncheon.

In 1836 he and another brother (William) sailed to Tunis for some big-game hunting; he returned to Curraghmore with three lion cubs, which he kept in his bedroom and trained to accompany him round the demesne like dogs.

Interestingly, he seems to have been one of the last – if not the last – Irish landowner to sponsor his own hurling team. Hurling is an ancient Irish field team sport; each team has fifteen players who play with a stick (hurl). The game is somewhat similar to hockey or lacrosse though at a much faster pace. It is reputedly the fastest field sport in the world. Brother L.P. Ó Caithnia, in his monumental Scéal na hIomána (The Story of Hurling), tells of a match in which the sponsors, Lord Beresford (sic) and Sir Thomas May, led their teams onto the pitch and then left them to slog it out.

EQUESTRIAN PURSUITS

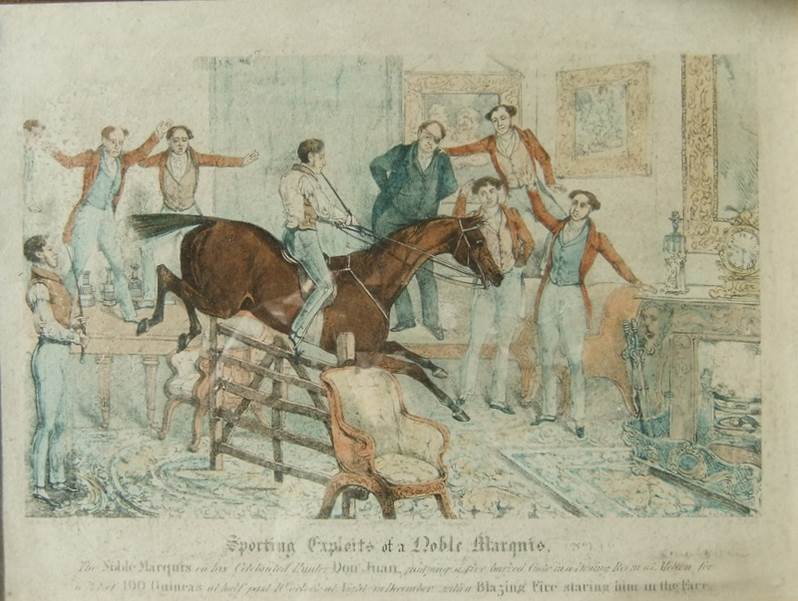

The Marquess’s most famous “freaks” (to use the contemporary word) were associated with horses. He assembled an impressive stable at Curraghmore, and raced at the Curragh and in England.

He himself rode in the 1840 Grand National, finishing third in a field of eleven (none of the others finished at all). In token of his association with the turf, a hornpipe was composed in his honour by the Tyneside fiddler and racing enthusiast James Hill. This print features a celebrated exploit in which he jumped his hunter Don Juan over a five-barred gate, the hard part being that this gate had been erected in the drawing-room of Lowesby Hall in Leicestershire, England, in front of a blazing fire.

The Hunter Don Juan

PAINTING THE TOWN RED

Painting the Melton Toll House

THE EGLINTON TOURNAMENT

Henry had grandiose intentions for Curraghmore, and commissioned the architect Daniel Robertson to draw up proposals for transforming the house into a huge neo-Gothic castle. Fortunately, these plans were never fulfilled. But in 1839 he was able to combine his passion for horses, Gothic, and extravaganza at the Eglinton Tournament, a medieval re-enactment held in Scotland and attended by vast crowds.

The Beresford crest being a dragon, Henry competed as the Knight of the Dragon – here he is with his entourage (the “friar” , incidentally, is his brother-in-law Viscount Ingestre). He is also depicted in his Eglinton armour in this miniature by Robert Thorburn at Curraghmore.

ROMANCE BLOSSOMS

At Eglinton, however, the daredevil Marquess was finally conquered – not by a fellow-knight but by the charms of this lady, the Honourable Louisa Anne Stuart, younger daughter of Lord Stuart de Rothesay.

She was in many ways his opposite: cultured, refined, artistic, sober, and deeply religious. He lost his heart to her, totally and irrevocably. The dragon had been tamed by the virtuous maiden – it was “the archetype of the ideals of chivalry embodied by the Eglinton Tournament”.

The knight, however, had to be worthy of his lady, and Henry had a lot of ground to make up. From now on, we read no more of mad pranks and drunken brawling. The lions were sold off to the Zoological Gardens in Regent’s Park. His energies became centred on fox-hunting, a sport which requires not only skilled horsemanship but careful planning, sound judgement, and hard work. As the Waterford Hunt was not available to him, he took over the mastership of the Tipperary Hounds, renting stables at Rockwell House (now Rockwell College).

He is the central figure in four prints entitled “The Noble Tips”, part of the series “Moore’s Tally-Ho to the Sports”. His hunting journal for the 1840s, published in 1901, shows meticulous attention to detail, every meet and hunt being carefully recorded. For keen history buffs, I recommend Dr Patrick Bracken’s recently published book on sport in nineteenth-century Tipperary.

SETTLING DOWN

The idyll lasted a week. One evening, he took Louisa out for a drive in his phaeton (a sporty open carriage made more for speed than comfort); the horses bolted, they were thrown out, and Louisa was seriously injured. Perhaps because of this, she was never able to have children. This near-tragedy shook Henry really badly and proved to be the turning-point in his life – he had so nearly lost the one thing that he loved above all else

STATELY WAYS

Henry and Louisa devoted themselves to the care of their estate. Proper houses were built for the six hundred workers and their families, schools and churches followed, the jungle-like gardens began to be transformed under Louisa’s hand.

The poor needed not only houses and food but clothing. Henry and Louisa established a woollen mill at the village of Kilmacthomas on their estate.

Sheep-farmers sold their wool to the mill, local women spun it into frieze, and the needy were issued with garments simply by subscribing a tiny sum to Louisa’s clothing club. Today, the older part of the mill at Kilmacthomas, (dating from Henry’s time), is now a car park; the remainder is about to be restored as a distillery – Louisa, a dedicated temperance campaigner, must be turning in her grave! The Marquess also used his political clout to have an extra workhouse for the county established at Kilmacthomas rather than in the mining village of Bunmahon on the Waterford coast.

THE IRISH FAMINE

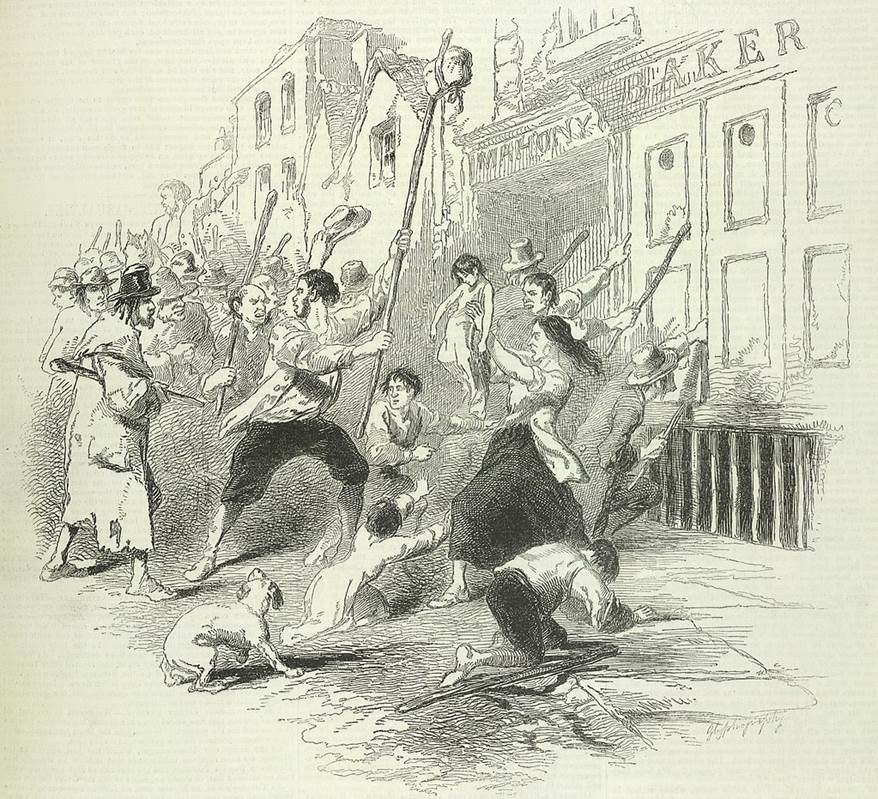

During the years of the Great Famine, the Curraghmore estate was spared scenes like this riot of starving people in nearby Dungarvan

Soup kitchens were set up, and the Marquess wrote to his agent in Ulster, ordering him to set up similar establishments in each of his northern parishes. The remark of Harney, the gamekeeper, on being instructed to kill off the precious stock of pheasants is often quoted: “His Lordship said he would make soup of the pheasants and buy meal for men and not for birds.”

In all of these humanitarian enterprises, the initiative may have come from Louisa – who generally gets all the credit – but they were put into effect by the organising skills of her husband.

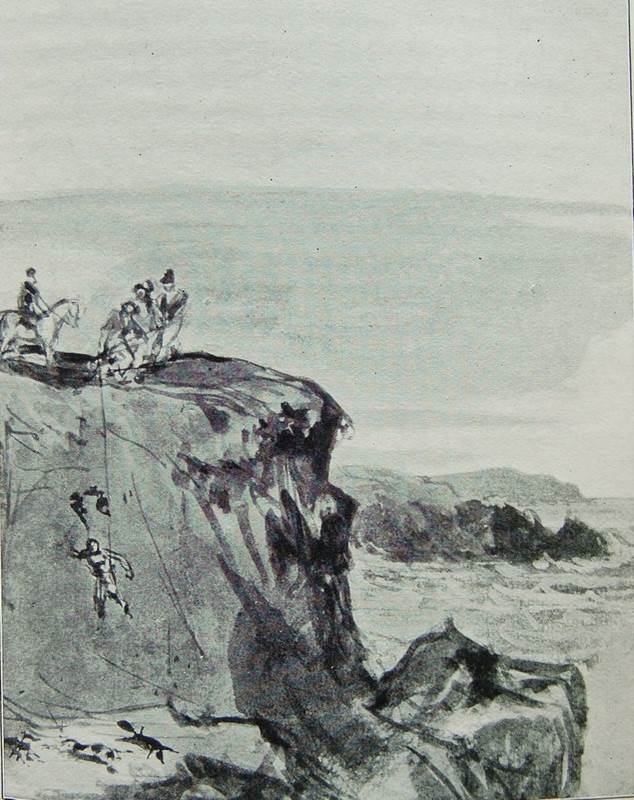

In 1843, after his stables in Tipperary were maliciously burned, the Marquess took over the Waterford Hounds instead. And so, fox-hunting continued, as did the journal; this sketch shows the rescue of some hounds that had fallen over a cliff while in pursuit of a fox near Stradbally.

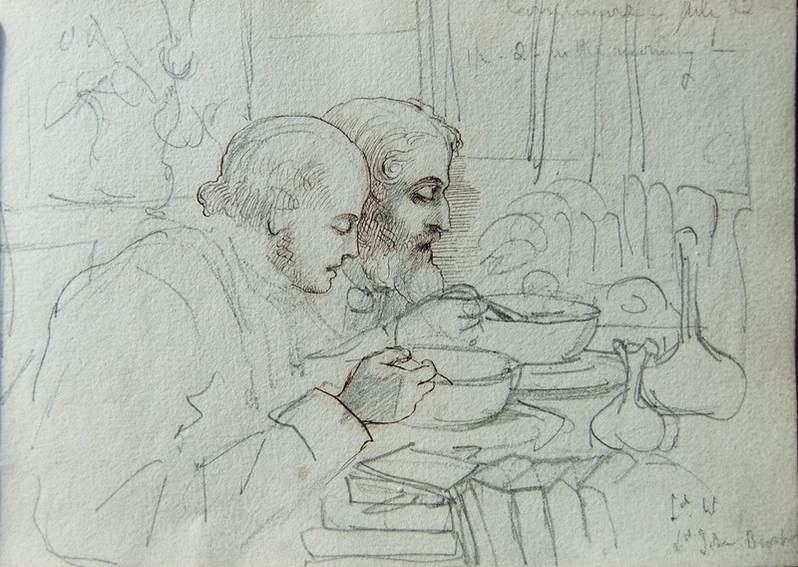

After the death of Henry’s brother William in 1850, his heir was his only surviving brother John, hero of the New York escapade, now (thanks to his uncle the Primate) rector of Mullaghbrack in County Armagh. He was the husband of Christiana Leslie (known in the family as Tina) of Castle Leslie, County Monaghan, and the father of four healthy sons. They were frequent visitors to Curraghmore. This sketch of the two brothers by Louisa shows them having supper after hunting at 2 a.m.

She outlived Henry by thirty-two years, busying herself with humanitarian and building works at Ford in Northumberland and Highcliffe in Hampshire, and corresponding with artists and critics such as Ruskin and Rossetti. She never returned to Ireland.

Johnny, Tina, and their sons now took over Curraghmore. The fourth marquess bullied his wife, flogged his children, and terrorised his household. It’s one thing to treat your family harshly – if you deal similarly with your tenants you will soon hit trouble.

He began by auctioning off his brother’s hunters and racehorses. Several of them had been painted by Samuel Spode, including the prize stallion Gemma di Vergy. Jemmy had been bought the previous year for £800; he was now sold for £1,050, British buyers beating off strong competition from Russian oligarchs. May Boy fetched only £91, perhaps because he was thought to be unlucky, and his wife May Girl went for even less.

Over the next few months, the new Marquess succeeded in undoing all the goodwill that had been built up by Henry and Louisa. That summer, his barns were burned and the crops of hay and corn destroyed. Three years later came a series of letters threatening assassination. This is the first:

“We give you notice that complaints are made that you are a Tyrant and a very bad Landlord and a bad man tho’ a Parson. In time MEND your ways in the County and be like your brother.”

The threats were never carried out: perhaps fortunately for all concerned, the fourth Marquess of Waterford died of gastro-enteritis after only seven years in charge.

Louisa commissioned the London-based Italian sculptor Carlo Marochetti to carve a life-size bronze effigy of her husband wearing the robes of a Knight of St Patrick for the family chapel at Clonegam.

She never saw it, but she also got Marochetti to carve a bust of Henry, which she kept beside her bed at Ford: “I think it excellent,” she wrote to a friend, “though the more like it is, the more one misses the life of the real face.” It’s now in the dining-room at Curraghmore.

The Waterford solicitor Robert Dobbyn wrote in his diary of the third Marquess: “He was a splendid man and very good and kind to me, a real sportsman.” The final word on Henry belongs perhaps to the unnamed local poet whose elegy was printed soon after the death of his hero:

What powers did haunt you through the sable gate

Immortal Marquis from your grand estate

And opened the doors of sorrow in this clime

Full forty years before your ageful time?

Too short he remained admired and half adored

The lamented Marquis of great Waterford.

Text: ©Julian Walton

Imagery: ©where shown

About: Julian C Walton MA FIGRS

Julian is a historian and Vice-President of The Irish Genealogical Research Society. A former school teacher and librarian, he writes and lectures regularly, particularly on topics connected with Waterford City and environs. Amongst his publications are The Royal Charters of Waterford and two volumes of On This Day, a series of short essays on Waterford’s history and heritage. He is currently delving through the archives of Curraghmore House with the aim of writing a definitive history of one of Ireland’s leading stately homes.

Julian’s Publications

Julian’s books are available at the following bookstores or online:

- The Royal Charters of Waterford – Available from the Waterford Treasures Museum Shop

or follow this online link. - On This Day – Available at The Book Centre, Waterford or online here

Curraghmore House

For details of public tours during the summer, please visit the Curraghmore website here

Let us inspire you more:

Curious to learn more? Hennessy & Furlong designs unique day and multi-day tours around Ireland. In the Waterford region, visits include many of the more authentic experiences such as VIP visits to Waterford Crystal and private visits to Curraghmore House. To discover possibilities for your trip, say hello here and let’s start discussing your ideas –> Contact Us

DISCOVER A HIDDEN IRELAND

Our Journal Writers are passionate about the special people and their special homes that inspire them to write and share their experiences. Join our club of fellow travellers and heritage enthusiasts reading their stories of discovery around Ireland.